Inertia

Inertia is the resistance of any physical object to any change in its state of motion, including changes to its speed and direction. It is the tendency of objects to keep moving in a straight line at constant velocity. The principle of inertia is one of the fundamental principles of classical physics that are used to describe the motion of objects and how they are affected by applied forces. Inertia comes from the Latin word, iners, meaning idle, sluggish. Inertia is one of the primary manifestations ofmass, which is a quantitative property of physical systems. Isaac Newton defined inertia as his first law in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which states:[1]

In common usage the term "inertia" may refer to an object's "amount of resistance to change in velocity" (which is quantified by its mass), or sometimes to its momentum, depending on the context. The term "inertia" is more properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his First Law of Motion: that an object not subject to any net external force moves at a constant velocity. Thus, an object will continue moving at its current velocity until some force causes its speed or direction to change.

On the surface of the Earth inertia is often masked by the effects of friction and air resistance, both of which tend to decrease the speed of moving objects (commonly to the point of rest), and gravity. This misled classical theorists such as Aristotle, who believed that objects would move only as long as force was applied to them

Classical inertia[edit]

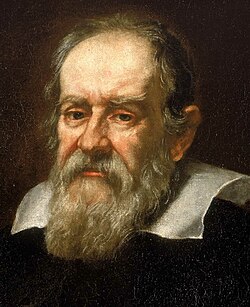

The law of inertia states that it is the tendency of an object to resist a change in motion. According to Newton, an object will stay at rest or stay in motion (i.e. 'maintain its velocity' in modern terms) unless acted on by a net external force, whether it results from gravity, friction, contact, or some other source. The Aristotelian division of motion into mundane and celestial became increasingly problematic in the face of the conclusions of Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, who argued that the earth (and everything on it) was in fact never "at rest", but was actually in constant motion around the sun.[11] Galileo, in his further development of the Copernican model, recognized these problems with the then-accepted nature of motion and, at least partially as a result, included a restatement of Aristotle's description of motion in a void as a basic physical principle:

Galileo writes that 'all external impediments removed, a heavy body on a spherical surface concentric with the earth will maintain itself in that state in which it has been; if placed in movement towards the west (for example), it will maintain itself in that movement'.[13] This notion which is termed 'circular inertia' or 'horizontal circular inertia' by historians of science, is a precursor to, but distinct from, Newton's notion of rectilinear inertia.[14][15] For Galileo, a motion is 'horizontal' if it does not carry the moving body towards or away from the centre of the earth, and for him 'a ship, for instance, having once received some impetus through the tranquil sea, would move continually around our globe without ever stopping'.[16][17]

It is also worth noting that Galileo later went on to conclude that based on this initial premise of inertia, it is impossible to tell the difference between a moving object and a stationary one without some outside reference to compare it against.[18] This observation ultimately came to be the basis for Einstein to develop the theory ofSpecial Relativity.

Concepts of inertia in Galileo's writings would later come to be refined, modified and codified by Isaac Newton as the first of his Laws of Motion (first published in Newton's work, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in 1687):

Note that "velocity" in this context is defined as a vector, thus Newton's "constant velocity" implies both constant speed and constant direction (and also includes the case of zero speed, or no motion). Since initial publication, Newton's Laws of Motion (and by extension this first law) have come to form the basis for the branch ofphysics known as classical mechanics.[citation needed]

The actual term "inertia" was first introduced by Johannes Kepler in his Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae (published in three parts from 1618–1621); however, the meaning of Kepler's term (which he derived from the Latin word for "idleness" or "laziness") was not quite the same as its modern interpretation. Kepler defined inertia only in terms of a resistance to movement, once again based on the presumption that rest was a natural state which did not need explanation. It was not until the later work of Galileo and Newton unified rest and motion in one principle that the term "inertia" could be applied to these concepts as it is today.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, despite defining the concept so elegantly in his laws of motion, even Newton did not actually use the term "inertia" to refer to his First Law. In fact, Newton originally viewed the phenomenon he described in his First Law of Motion as being caused by "innate forces" inherent in matter, which resisted any acceleration. Given this perspective, and borrowing from Kepler, Newton actually attributed the term "inertia" to mean "the innate force possessed by an object which resists changes in motion"; thus Newton defined "inertia" to mean the cause of the phenomenon, rather than the phenomenon itself. However, Newton's original ideas of "innate resistive force" were ultimately problematic for a variety of reasons, and thus most physicists no longer think in these terms. As no alternate mechanism has been readily accepted, and it is now generally accepted that there may not be one which we can know, the term "inertia" has come to mean simply the phenomenon itself, rather than any inherent mechanism. Thus, ultimately, "inertia" in modern classical physics has come to be a name for the same phenomenon described by Newton's First Law of Motion, and the two concepts are now considered to be equivalent.

Relativity[edit]

Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity, as proposed in his 1905 paper, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," was built on the understanding of inertia andinertial reference frames developed by Galileo and Newton. While this revolutionary theory did significantly change the meaning of many Newtonian concepts such asmass, energy, and distance, Einstein's concept of inertia remained unchanged from Newton's original meaning (in fact the entire theory was based on Newton's definition of inertia). However, this resulted in a limitation inherent in special relativity that the principle of relativity could only apply to reference frames that wereinertial in nature (meaning when no acceleration was present). In an attempt to address this limitation, Einstein proceeded to develop his general theory of relativity("The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity," 1916), which ultimately provided a unified theory for both inertial and noninertial (accelerated) reference frames. However, in order to accomplish this, in general relativity Einstein found it necessary to redefine several fundamental concepts (such as gravity) in terms of a new concept of "curvature" of space-time, instead of the more traditional system of forces understood by Newton.[19]

As a result of this redefinition, Einstein also redefined the concept of "inertia" in terms of geodesic deviation instead, with some subtle but significant additional implications. The result of this is that according to general relativity, when dealing with very large scales, the traditional Newtonian idea of "inertia" does not actually apply, and cannot necessarily be relied upon. Luckily, for sufficiently small regions of spacetime, the special theory can be used, in which inertia still means the same (and works the same) as in the classical model.[dubious ]

Another profound conclusion of the theory of special relativity, perhaps the most well-known, was that energy and mass are not separate things, but are, in fact, interchangeable. This new relationship, however, also carried with it new implications for the concept of inertia. The logical conclusion of special relativity was that if mass exhibits the principle of inertia, then inertia must also apply to energy. This theory, and subsequent experiments confirming some of its conclusions, have also served to radically expand the definition of inertia in some contexts to apply to a much wider context including energy as well as matter.[citation needed]

Interpretations

Mass and inertia

Physics and mathematics appear to be less inclined to use the popular concept of inertia as "a tendency to maintain momentum" and instead favor the mathematically useful definition of inertia as the measure of a body's resistance to changes in velocity or simply a body's inertial mass.

This was clear in the beginning of the 20th century, when the theory of relativity was not yet created. Mass, m, denoted something like an amount of substance or quantity of matter. And at the same time mass was the quantitative measure of inertia of a body.

The mass of a body determines the momentum  of the body at given velocity

of the body at given velocity  ; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

of the body at given velocity

of the body at given velocity  ; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

The factor m is referred to as inertial mass.

But mass, as related to the 'inertia' of a body, can also be defined by the formula:

Here, F is force, m is inertial mass, and a is acceleration.

By this formula, the greater its mass, the less a body accelerates under given force. Masses  defined by formula (1) and (2) are equal because formula (2) is a consequence of formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and velocity. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of a body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

defined by formula (1) and (2) are equal because formula (2) is a consequence of formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and velocity. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of a body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

defined by formula (1) and (2) are equal because formula (2) is a consequence of formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and velocity. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of a body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

defined by formula (1) and (2) are equal because formula (2) is a consequence of formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and velocity. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of a body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

This meaning of a body's inertia therefore is altered from the popular meaning as "a tendency to maintain momentum" to a description of the measure of how difficult it is to change the velocity of a body. But it is consistent with the fact that motion in one reference frame can disappear in another, so it is the change in velocity that is important.

Inertial mass[edit]

There is no measurable difference between gravitational mass and inertial mass. The gravitational mass is defined by the quantity of gravitational field material a mass possesses, including its energy. The "inertial mass" (relativistic mass) is a function of the acceleration a mass has undergone and its resultant speed. A mass that has been accelerated to speeds close to the speed of light has its "relativistic mass" increased, and that is why the magnetic field strength in particle accelerators must be increased to force the mass's path to curve. In practice, "inertial mass" is normally taken to be "invariant mass" and so is identical to gravitational mass without the energy component.

Gravitational mass is measured by comparing the force of gravity of an unknown mass to the force of gravity of a known mass. This is typically done with some sort of balance. Equal masses will match on a balance because the gravitational field applies to them equally, producing identical weight. This assumption breaks down near supermassive objects such as black holes and neutron stars due to tidal effects. It also breaks down in weightless environments, because no matter what objects are compared, it will yield a balanced reading.

Inertial mass is found by applying a known net force to an unknown mass, measuring the resulting acceleration, and applying Newton's Second Law, m = F/a. This gives an accurate value for mass, limited only by the accuracy of the measurements. When astronauts need to be measured in the weightlessness of free fall, they actually find their inertial mass in a special chair called a body mass measurement device (BMMD).

At high speeds, and especially near the speed of light, inertial mass can be determined by measuring the magnetic field strength and the curvature of the path of an electrically-charged mass such as an electron.

No physical difference has been found between gravitational and inertial mass in a given inertial frame. In experimental measurements, the two always agree within the margin of error for the experiment. Einstein used the fact that gravitational and inertial mass were equal to begin his general theory of relativity in which he postulated that gravitational mass was the same as inertial mass, and that the acceleration of gravity is a result of a 'valley' or slope in the space-time continuum that masses 'fell down' much as pennies spiral around a hole in the common donation toy at a chain store. Dennis Sciama later showed that the reaction force produced by the combined gravity of all matter in the universe upon an accelerating object is mathematically equal to the object's inertia [1], but this would only be a workable physical explanation if by some mechanism the gravitational effects operated instantaneously.

At high speeds, relativistic mass always exceeds gravitational mass. If the mass is made to travel close to the speed of light, its "inertial mass" (relativistic) as observed from a stationary frame would be very great while its gravitational mass would remain at its rest value, but the gravitational effect of the extra energy would exactly balance the measured increase in inertial mass.

Inertial frames[edit]

In a location such as a steadily moving railway carriage, a dropped ball (as seen by an observer in the carriage) would behave as it would if it were dropped in a stationary carriage. The ball would simply descend vertically. It is possible to ignore the motion of the carriage by defining it as an inertial frame. In a moving but non-accelerating frame, the ball behaves normally because the train and its contents continue to move at a constant velocity. Before being dropped, the ball was traveling with the train at the same speed, and the ball's inertia ensured that it continued to move in the same speed and direction as the train, even while dropping. Note that, here, it is inertia which ensured that, not its mass.

In an inertial frame all the observers in uniform (non-accelerating) motion will observe the same laws of physics. However observers in another inertial frame can make a simple, and intuitively obvious, transformation (the Galilean transformation), to convert their observations. Thus, an observer from outside the moving train could deduce that the dropped ball within the carriage fell vertically downwards.

However, in reference frames which are experiencing acceleration (non-inertial reference frames), objects appear to be affected by fictitious forces. For example, if the railway carriage were accelerating, the ball would not fall vertically within the carriage but would appear to an observer to be deflected because the carriage and the ball would not be traveling at the same speed while the ball was falling. Other examples of fictitious forces occur in rotating frames such as the earth. For example, a missile at the North Pole could be aimed directly at a location and fired southwards. An observer would see it apparently deflected away from its target by a force (the Coriolis force) but in reality the southerly target has moved because earth has rotated while the missile is in flight. Because the earth is rotating, a useful inertial frame of reference is defined by the stars, which only move imperceptibly during most observations.The law of inertia is also known as Isaac Newton's first law of motion.

In summary, the principle of inertia is intimately linked with the principles of conservation of energy and conservation of momentum.

Source of inertia; speculative theories[edit]

Various efforts by notable physicists such as Ernst Mach (see Mach's principle), Albert Einstein, Dennis William Sciama, and Bernard Haisch have been put towards the study and theorizing of inertia. "An object at rest tends to stay at rest. An object in motion tends to stay in motion."

Rotational inertia[edit]

Another form of inertia is rotational inertia (→ moment of inertia), which refers to the fact that a rotating rigid body maintains its state of uniform rotational motion. Itsangular momentum is unchanged, unless an external torque is applied; this is also called conservation of angular momentum. Rotational inertia depends on the object remaining structurally intact as a rigid body, and also has practical consequences; For example, a gyroscope uses the property that it resists any change in the axis of rotation.